The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

SAHIPATA (ISHAKLI) HAN

A han with a commanding kiosk mosque in its courtyard and separate bath and fountain to the rear. Built by the most important Seljuk architectural patron ever known, it stood strong in the face of a powerful earthquake in 2002.

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 252; photo I. Dıvarcı |

|

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

|

View of main entry portal (pre-2009 restoration) |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

|

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 261; photo I. Dıvarcı |

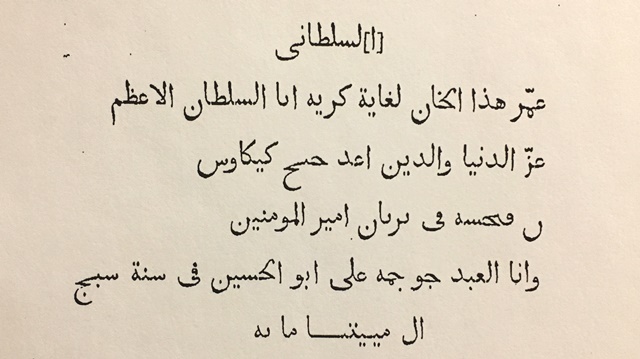

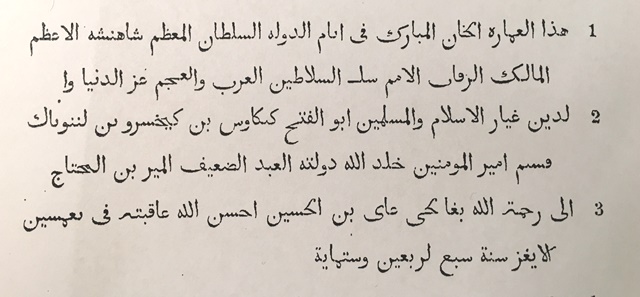

inscription over the covered section door |

inscription over the main door into the courtyard |

drawing by Huart |

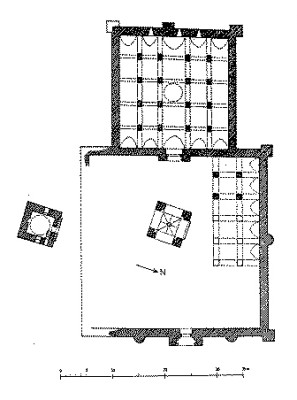

plan drawn by Erdmann |

View showing kiosk mosque in courtyard and group of side cells |

Kiosk mosque and view of portal leading to covered section |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 259; photo I. Dıvarcı |

photo by Ibrahim Divarci; used by permission |

|

|

mihrab of the kiosk mosque |

star vault of the kiosk mosque |

Group of side cells in courtyard |

|

Eravşar, 2017. p. 257; photo I. Dıvarcı |

DISTRICT

03 AFYONKARAHISAR

LOCATION

38.532712, 31.228529

The Sahipata Han is located on the Afyon-Akşehir Road, about 67 km east of Çay right in the center of the town of Sultandağı.

No

traces of the old caravan route, which probably passed in front of the

courtyard, remain. The road, which goes towards Afyonkarahisar, forms a junction

where two caravan roads intersect in the direction of Bolvadin after Çay. The

road on which the caravanserai was built was mentioned in Ottoman archives as an

army road.

Nasuh, also known as Matrakci, the Ottoman imperial mathematician and mapmaker to Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, Selim II, and Murad III, also provided a description of the road and how it was used.

NAMES

Sultandaği-Işakli Han

Seljuk period sources do not make any

mention of the name of the han and the name is not mentioned in the inscription.

The area of the han was mentioned as a stopover station in the 17th and 18th

centuries. Katip Çelebi, the 17th century Ottoman historian and

geographer, is the first person to mention the han. Katip Çelebi, describing the

village of Sultandaği at that time, said: It is a leagues distance from

Akşehir, to the west of a large road, in a village heading east. There is a han

for passengers.

Numerous travelers have mentioned the han in their journals. These include Hamilton, Sarre and Oberhummer and Zimmerer. An interesting account is left by the Frenchman Clément Huart, who travelled to Konya along this road in the 19th century. He mentioned the han and read its inscription. Huart related this information about Ishakli in his travelogue, Konya, la ville des derviches tourneurs, as follows:

A midday meal was prepared for us in a coffeehouse in Işakli. If you can imagine such a thing, it consisted of a terrace with a packed dirt floor, looking over the only street of the city, and wide open on all sides. There were a few cushions scattered on a bench, and in the middle was a round wooden platter set on two boards which served as legs. On the platter were two or three copper-plated bowls covered with high lids, and next to each guest was placed a roll, a sort of a soft bread without crust or crumbs, and a horn spoon. A crowd of all types of people had gathered here, all who had invited themselves: travelers, gendarmes, stable boys and village notables. In the copper dishes were all sorts of unbelievable soups and extraordinary fried eggs. And such is a magnificent meal at the village of Işhakli

Erdmann believes that a previous han existed at this site before the present one was built.

DATE

1249-50 (est)

REIGN OF

Izzeddin Keykavus II

INSCRIPTION

An inscription is found on both crown doors of the two main sections of the han.

The inscription over the covered section door reads as follows:

It was built in the time of Izzeddin Al Dunya, the son of Keyhüsrev, the son of Alaeddin Keykubad, his humble slave Ali ibn Husain.

When Clément Huart read the inscription in 1895, he added a date of 607 (1210) at the end of the inscription, but he must have been mistaken.

There is another inscription over the courtyard door which states the same information, but qualifies Sahip Ata as "His humble slave who has sinned".

The inscription over the courtyard door was read by Huart as follows:

Has built this blessed han, during the reign of the magnificent sultan of Sultans, victor of the people, sultan of the Arabs and the Persians, Izzeddin, defender of the Faith, the victorious Kaykhavus, son of Keyhosrau, son of Kaykubad, the Prince of the believers (May Allah protect his empire for all eternity!), by his weak slave, El-Mir, son of he who needs the clemency of Allah, Boha .Ali, Son of El-Hoseyn (may God reserve him a sweet death!) in the year of the Pig of the Uighurs, 647 (1249).

He goes on to say that the year 647 corresponds to 16 April 1249, which corresponds to the reign of Izzeddin Keykavus II.

PATRON

The Seljuk vizier Fahreddin Ali ibn

Husein (Fakhr al-Din Ali ibn al-Husayn ibn Abu Bakr) known as Sahipata (d.

1288), as indicated in the inscription.

A special word is in order concerning the builder of this han. He was one of the most important and powerful Seljuk statesmen of the period of the Mongol Protectorate (after 1243), holding a succession of high offices in the Seljuk administration between 1250-51 and his death in 1288. He is the last of the great statesmen figures of the Seljuk period, along with Celaleddin Karatay and Shams al-din Isfahani.

Few Seljuk era patrons loomed larger than Sahip Ata. He is a significant figure, not only in Seljuk history as a successful statesman, but also in Seljuk architecture as a distinguished donor. Sahip Ata is considered the greatest Seljuk patron of architecture of the post-Kösedağ era of the second half of the thirteenth century. He initiated the construction of a considerable number of buildings, as indicated in written sources such as foundation charter. He was called Sahip-Ata ("Lord of Giving") and was given the title Abu al-Khayrat ("Father of Good Works").

After the defeat of the Seljuks at the hands of the Mongols at the Battle of Kösedağ in 1243, the Seljuk state became dismantled under their authority. The weak Giyaseddin Keyhüsrev lost all absolute power for the sultanate, and the reigns of the government were taken over by upper ranking statesmen, bureaucrats and viziers, notable Karatay, Sahip Ata and Muineddin Pervane. These statesmen had to tread difficult waters, trying to placate the Mongols and keeping a semblance of order for the people. Sahip Ata was particularly successful in trying to maintain stability and normalcy by his policies, in part due to his intense construction program.

The career of this statesman is well-documented. He was originally from the Nadir district of Akşehir, which is known as Atakent today. He became minister of justice after the legendary Karatay died in 1258. His rise was meteoric: in two years the Seljuk Sultan Izzeddin Keykavus II appointed him as sahip, or Grand Vizier, in 1260. He carved out his own mini-realm of power in the west of Anatolia near Sultandağ, far from the watchful eyes of the Mongols. He tried to hold the Seljuk state together along with the wily Muineddin Pervane of Tokat. However, their collaboration ceased in 1271, when Pervane, estimating that Sahip Ata had become too powerful and wishing to take all control of the Empire for himself, locked Sahip Ata up in prison. However, the Mongol Khan Abaka appointed him once more as Grand Vizier in 1271, putting him in charge of the management of all his properties.

The region of Karahisar on the western frontier was conferred on him and his family at the beginning of the Mongol period, and he carved out his own mini-realm of power in the west of Anatolia here, far from the watchful eyes of the Mongols. The Seljuk historian Ibni Bibi relates that he gave Ladik, Honaz (the ancient Chonai) and Afyonkarahisar to his sons, and that his descendants held sway in Afyon until the middle of the 14th century. Both he and his sons appear to have been particularly active as builders. He built a fountain and a mosque in his hometown. The mosque collapsed in the 1980s, but its inscription remains.

The last Seljuk Sultan, Mesud II, eldest son of former Sultan Izzeddin Keykavus II, established himself as sultan in Kayseri in 1283. He ruled over the undivided territory of the Seljuk Sultanate, though with no real power, since he was merely a puppet and vassal of the Mongol khan Arghun. What little power the Seljuks had was held by the Sultan's vizier, Sahip Ata Fahrettin Ali. Sahip Ata returned to Konya and continued to govern until the Ilkhanids forced him to withdraw in 1285.

He retired to Akşehir and died there in November, 1288, after a career of more than 40 years in Seljuk government, which never saw his likes again.

It is obvious that Sahip Ata loved buildings and building. He is the largest donor of monumental works of architecture in the Seljuk Empire. The range of his buildings is varied in scope, and he took pains to recruit the leading architects, Kölük bin Abdullah and Kaluyan el-Konevi on his projects. He put his personal fortune to good use, building numerous monuments in the Akşehir region. His patronage has graced Turkey with three of its most impressive and beautiful monuments: the Konya Larende Sahip Ata Complex, the Sivas Gök Medrese and the Konya Ince Minare.

Sahip Ata lived a fabled life, but also a sad one. His four sons all preceded him in death. Two of them, Nüsretüddin Hasan and Taceddin Hüseyin, lost their lives in the siege of Konya led by Karaman Mehmet in 1277. Legend has it that the master architect Kölük bin Abdullah engraved the sorrow of the vizier into the tiles of the Sahipata Medrese in Konya.

His patronage of 40 years is unmatched by any other statesman or sultan. In the Manaqib al-arifin of Shams al-Din Aflaki, the story is told that after Sahip Ata's death, one of his companions saw him in a dream and said to him, "They call you the Abu al-Khayrat ("Father of Good Works"). What rewards did you find in the after-life?" Sahip Ata answered by pointing put that he had received no reward for what he had done, and that the only reward for his generosity was that a tree from his property was used to build a part of the tomb of Celaleddin Rumi.

There are in sum eleven buildings epigraphically attested to this patron:

Ishakli Han and Complex (1249)

Taş Medrese in Akşehir (1250) (restoration of original 1216 building)

Akşehir Hanikah (1260-61)

Konya Larende Sahipata Mosque and complex (tomb, bath, fountain, shops, hanikah) (1258-1284)

Konya Inci Minareli Medrese (1258-79)

Han at Ilgin (no longer standing)

Bath Complex at Ilgin (1267, no longer extant)

Sahibiye Fountain (1266) and Medrese (1267) in Kayseri

Gök Medrese in Sivas (1271)

The Havzan Icehouse in Konya (one of the 3 Seljuk icehouses in Konya; undated; located across from the Konya train station; under restoration in 2019)

There are 5 other buildings associated with him, including the Ince Minareli Medrese in Konya. This han is believed to be the first han that he built.

Bilici states that the han was built by one of Sahip Ata's sons, not the Vizier himself; however, it is most likely to have been built by the father, an impressive builder.

BUILDING TYPE

Covered section with an open courtyard (COC)

Covered

section is smaller than the courtyard

Covered section with 5 naves (a middle nave and 2 lateral aisles) perpendicular

to the rear wall

5 lines of support vaults parallel to the rear wall

DESCRIPTION

The han faces west, and lies perpendicular to the

road. The entrance door

is to the north.

The han comprises the traditional Seljuk plan with a covered section and a courtyard surrounded by service areas in front of it. The covered section is smaller than the courtyard and is placed to the south of it, complete with a free-standing kiosk mosque in the middle of the courtyard.

The han was constructed with smooth cut stone blocks, with very thick walls. The walls were built using the rubble wall technique. Pitch-faced stones were used in the arches and vaults, and the lantern dome was made of brick.

Courtyard:

Most of the walls of the han were in ruins before the last restoration, except for the outer walls of the courtyard and the section in the west corner is comprised of an open arcade with three sections formed by two aisles of cells, covered by pointed vaults in the direction of the courtyard.

Six rooms line the southeast (left) side of the courtyard, separated by a central space in the form of an iwan which opens directly into the courtyard. The iwan gives access to the block of two rooms on both sides of it. The two rooms in the corners are entered directly from the courtyard. Another room is located on the south corner outside these interconnected rooms. It is not known what these rooms were used for; but it is believed they were service areas such as the kitchen, storerooms and treasury. The courtyard was paved with dressed stones. Most of the spaces of the courtyard collapsed in the 1960s and were subsequently repaired around 1975 and also during the most recent renovation in 2008.

The spaces in entrance side of the courtyard have collapsed, so it is not entirely possible to reconstitute the plan. The entrance door opening is in the form of an iwan, with two square rooms of approximately the same size on each side of it. The room in the northeast corner is rectangular and its door opens onto the courtyard. Archeological investigation carried out in 2003 showed that there were five rooms on both sides of the entrance on the northwest, and that there were seven rooms along the southeast side of the courtyard.

The crown door of the courtyard service area is more elaborate than the crown door of the covered section. The crown door of the courtyard projects forward in the northeast direction from the main bearing wall. The crown door composition is composed of seven rows of muqarnas framed by different borders surrounding the main door. One of the five borders surrounding the muqarnas has half-star decorations, while others are plain. Above is the rectangular inscription plaque and rosettes with geometric patterns on the sides.

The courtyard is reinforced by two rectangular support towers on the side walls, two half circular towers on the front side and three square support towers on the corners. There was probably a tower in the south corner as well, but this section has collapsed.

Mosque: The kiosk mosque is located in the middle of the courtyard, and is the last known example of a free-standing kiosk mosque built in the Seljuk period. It is raised above the ground on four L-shaped piers, connected by pointed arches. The area underneath is covered with star vault. The mosque is turned 20 degrees to orient it correctly in the qibla direction. There are also traces of a well in the middle of the courtyard to draw water for performing the ritual ablutions before prayer. Windows are set in the east and west walls of the mosque, and are surmounted by four rows of muqarnas. Entry to the mosque is via a double staircase with console steps set on the north side and which climbs following the arch surfaces. A beautiful architrave lintel has been set over the entrance door and forms a part of the decorative program of the crown door. Five rows of muqarnas rise above the flat lintel window opening.

The interior of the square mosque is covered with an attractive muqarnas star vault, which has suffered damage over the years. The mihrab is located opposite the entrance. Three frames surround the mihrab niche and is framed by six rows of muqarnas and two columns with cubic capitals. A staircase of three steps in the north corner leads to the roof of the mosque.

Covered section:

The han is built with the classical covered section with open courtyard plan. The covered section of the han is practically square in shape. It consists of five naves placed vertically towards the rear wall in the northeast direction. The naves are composed of four support lines connected to each other by five pointed arches carried on four piers in each. The middle nave is higher and wider than the side naves. A dome, sitting on brick corner squinches, is located between the second and third support lines of the middle nave, over the transept at the intersection of the middle nave in the northeast-southwest direction and the central nave in northwest-southwest direction. Each side of the drum was outfitted with a window to illuminate the interior. The lantern dome was damaged during the restoration in 1970.

The 16 piers carrying the naves are square. Lighting is provided by two slit windows on the southeast wall, opening between the second and fourth arch supports, and three slit windows facing the central nave on the southwest wall on both sides of the naves. Excavations were carried out during the renovation of the Sahip Ata Caravanserai but the loading platforms in the covered section were not discovered. However, Dr. Osman Eravşar discovered a tanduri oven set haphazardly in a corner of the covered section during a visit in 2007. This tanduri oven was probably originally located in the platform section.

The restored crown door of the building projects inwards about 1 m from the outer south wall. The crown door opening is composed of a half-circular arch composed of interlaced stones supported by consoles at the sides. There are scallop shells in the corners of the interior section of the crown door, above which is the rectangular inscription plaque. As generally seen in Seljuk portals, there is a niche on both lateral faces of the crown door opening, surmounted by 3 rows of muqarnas.

EXTERIOR

The exterior walls of the covered section are braced by five support towers each, one in the middle of each of the three outer sides of the walls of the covered section, and two on the corners.

A distinguishing feature of this han is that it has a separate bath, fountain and mosque to the rear. As such, it forms a mini-complex with the han, much like those seen around a medrese in the Seljuk era. This area to the rear of the han is a lively spot for local merchants and farmers to tether their wagons and share conversation and tea under the trees.

Bath: The Çifte Baths are located outside of the mosque to the northwest, with an adjoining mosque and fountain. The construction date of the bath is unknown, but it displays the characteristic features of Seljuk period, and is believed this to have built at the same time as the han. It is fairly rare for hans to include baths inside or outside of the han. Other examples include the Kargi and Ağzikara Hans. The bath consists of a changing room with a square plan, leading to the tepedarium (warm) room which is covered with a barrel vault in northwest-southeast direction. From here, a door leads to the caldarium (hot room), comprised of two square rooms of the same size and covered with a dome. The water tank is situated next to the hot room northwest of the bath with the furnace behind it. The baths collapsed in 1980, but were later rebuilt.

Fountain: The Laleli Fountain, a single-sided street type, most likely originally dates from the Seljuk era and was built at the same time as the baths. However, it was replaced during the Ottoman period by the existing fountain, probably after the 17th century. The fountain is framed by a pointed arch. Reuse spolia piece can be seen on the dedication stone of the fountain. A Seal of Suleiman (Star of David) motif is set inside a rosette on the keystone of the arch. A carved vase with a flower, an Ottoman era stylistic device, can be seen on the dedication stone.

Mosque:

The mosque is composed of a single nave. According to its inscription, it was built in the time of the Karamanoğlu Ibrahim Bey in 1458. It was completely rebuilt in the 19th century. It collapsed in 1912 and the Ulu Mosque (Çarşi Mosque-Aşaği Mosque) was built to replace it. Only the minaret remains from the old mosque.

BUILDING MATERIALS

Some reuse spolia materials were used, notably above the kiosk mosque and the architrave used as a lintel over the entrance. Spolia material was used sparingly in some of the important parts of the building, as compared to the more extensive use in other hans. There are some spolia stones on the the walls of the han.

The entrance door to this mosque displays a unique and remarkable use of spolia. A marble architrave piece was placed on top of the door span as a lintel, just below the row of muqarnas. On the front surface of the architrave there are relief palmettes with circular knobs in the background. A piece with religious figures is placed below the lintel part of the architrave.

However, most of the spolia materials were used in the kiosk mosque which stands in the middle of the court. On the southeast side of the mosque is a marble sarcophagus lid with palmette leaves in its corners and which is almost level with the eaves. It is estimated that this lid dates from the 2nd century, and may be a part of the piece used on the main portal of the mosque. The definite placement of these highly-decorative pieces was intentional for the decorative scheme of the mosque, and brings a sense of grace and movement to the façade. The plain inner surface of the sarcophagus was used as the surface of the inscription, and the rear side of the spolia, the original outer face, has been preserved as it faces the inner part of the portal.

Mason marks can be seen on some of the stones used in the walls.

DECORATION

The building is not particularly rich as concerns decoration. The most significant decorative elements are the rows of muqarnas on the crown doors and the star vault in the kiosk mosque.

DIMENSIONS

Total area: 1800m2

Area of

covered

section: 440 m2

Area of courtyard: 1,100m2

STATE OF CONSERVATION, CURRENT USE

The vaults and dome were repaired during the restoration made in the 19th century, and the lantern dome was repaired in 1884. The han was repaired in 1970 and the roof was rebuilt. Unfortunately, humidity has occurred due to the porous stone material used during the restoration.

Sultandağı was the epicenter of a magnitude 6.0 earthquake on February 3-4, 2002, which destroyed much of the town's center. Although the han remained standing, it was damaged severely. The kiosk mosque walls and vault stones composing the support system cracked. The pavement of the other sections of the han collapsed, the wall surfaces cracked and the floor suffered subsidence. The work to repair the damaged and ruined parts caused by the earthquake was led by Dr. Dicle Aydin of the Selcuk University in Konya. This restoration project, which started in 2005, was completed in 2009. Most of the work involved stone-by-stone reassembly of the kiosk mosque. The work was completed, to a large extent, in 2008.

The han is now in good shape. It is run as an open-air museum by the Turkish government and is open for visits.

This han has been thoroughly researched by Dr. Dicle Aydin, Assistant Professor of Architecture at the Selcuk University at Konya. Her research was published (in Turkish) in the March 2006 issue of the Journal of Academic Studies of Turkish Islamic Civilisation. I would like to thank Dr. Aydin for giving me the permission to reproduce her article on this webpage. It contains an extensive bibliography in Turkish.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Akalın, Ş. Anadolu Selçuklu Kervansaraylarinda Kösk Mescitler. » Sanat Tarihi Araştirmalari Dergisi 1, 1987, pp. 3-7.

Aflaki, Shams al-din Ahmed. (1976). Manakib al-arifin. Turkish edition edited by Tahsin Yazici, Ankara, 502.

Aflaki, Shams al-din Ahmed. (2002). Manakib al-arifin. English edition translated by John OKane as The Feats of the Knowers of God. Leiden, 346.

Akok, Mahmut. Ishakli Kervan Sarayi. Türk Arkeologi Dergisi (21) (1), 1974, pp. 5-21.

Altun, Ara. An Outline of Turkish Architecture in the Middle Ages, 1990, p. 200.

Arat, Y. Afyon Sultandaği Sahip Ata Kervansarayi. Türk Islam Medeniyeti Akademik Araştirmalar Dergisi (2), 2006, pp. 77-112.

Bayrak, M. O. Türkiye Tarihi yerler kılavuzu, 1994, p. 28.

Bilici, Z. Kenan. Anadolu Selçuklu Çaği Mirası. Mimarı = Heritage of Anatolian Seljuk Era. Architecture. 3 vols. Ankara: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı: Selçuklu Belediyesi, 2016, vol. 1, pp. 86-89.

Eravşar, O. Spolia in Seljuk Buildings. in SOMA 2014: Proceedings of the 18th Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology. Wroclaw, 2014, pp. 167-182.

Eravşar, Osman. Yollarin Taniklari (Witnesses of the Way), 2017, pp. 252-261.

Erdmann, Kurt. Das Anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jahrhunderts, 1961, pp. 143-145, no. 38; vol. 3, pp. 157-161.

Ferit, M. & Mesut, M. Selçuk Veziri Sahip Ata ile Oğullarinin Hayat ve Eserleri. Istanbul, 1934, p. 97.

Görür, Muhammet. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari Kataloğu. Acun, H. Anadolu Selçuklu Dönemi Kervansaraylari. Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanliği, 2007, p. 505.

Hamilton, W. Researches in Asia Minor, 1842, p. II, 183.

Huart, C. Epigraphie arabe dAsie mineure. Paris, 1895, pp. 15-23.

Huart, Clément. Konya, la ville des dervishes tourneurs: souvenirs dun voyage en Asie Mineur, 1897, pp. 100-109.

Ilgar, Y. & Karazeybek, M. Afyonkarahisarda Camii ve Mescitler. Afyon Kütüğü, vol. 1, 2005, p. 327.

Ilter, İsmet. Tarihi Türk Hanları. Karayolları Genel Müdürlüğü Publication, Ankara 1969.

Karpuz, Haşim. & Kuş, A. & Dıvarcı, I. & Şimşek, F. Anadolu Selçuklu Eserleri, 2008, p. 52.

Karpuz, H. Sahip Atanin Yaptirdiği Işakli Han. Antalya 3, Selcuklu Semineri Bildikeri. Istanbul, 1989.

Kiepert, R. Karte von Kleinasien, in 24 Blatt bearbeitet, 1902-1916.

Matrakchi, N.S. Beyhan-i Menzil-i Sefer-i Irakeyn. Ankara, Turk Tarih Kurumu, 2014.

Oberhummer, R. & Zimmerer, H. Durch Syrien und Kleinasien, 1898, p. 409.

Özergin, M. Kemal. Anadoluda Selçuklu Kervansarayları, Tarih Dergisi, XV/20, 1965, p. 153, n. 55; p. 160, n. 103.

Rennel, J. Illustrations (chiefly geographical) of the History of the Expedition of Cyprus. London, 1816, p. 32.

Rice, Tamara Talbot. The Seljuks in Asia Minor, 1961, p. 206.

Taeschner, F. Osmanli Kaynaklarina gore Anadolu Yollari, 1924. Translated by TKK Kütüphanesi Basilmamiş Tercümeler, no, 131, 2010.

Uysal, Mehmet, Aydın, Dicle, Çınar, Kerim and Arat, Yavuz. "Afyon Sultandağı Sahip Ata Kervansarayı." Turk-Islam Medeniyeti Akademik Araştirmalar Dergisi 2, March 2006, pp. 77-112. (I would like to thank Dr. Aydin for giving me the permission to reproduce her article on this webpage).

Üyümez, M. & Kaya, F. Afyonkarahisarda Su Mimarasi. Afyon Kütüğü, vol. 1, 2005, p. 407.

Wolper, Ethel Sara. (2005). Understanding the public face of piety: philanthropy and architecture in late Seljuk Anatolia. Mésogeios 25-26, 311-336.

|

The Seljuk era Çifte Baths to the rear of the han

|

plan of Seljuk era bath to the rear of the han

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

©2001-2025, Katharine Branning; All Rights Reserved.