The Seljuk Han of Anatolia

Kurt Erdmann

(1901-1964)

photos courtesy of Robin Wimmel ;

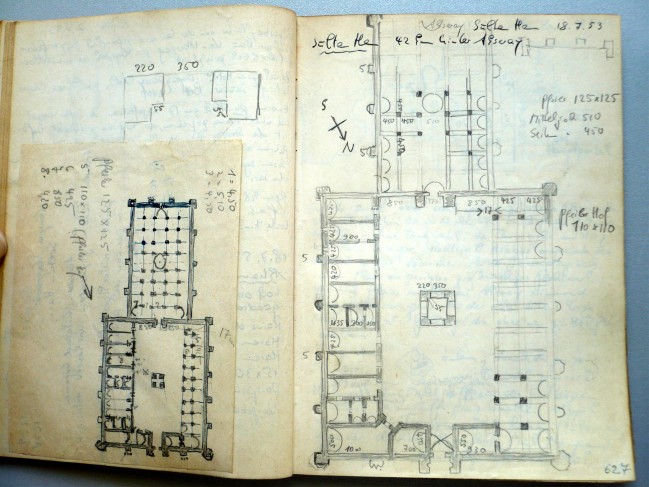

photos from the Tagebücher 1951-1958: 37 volumes of unpublished handwritten diaries concerning the travels of Erdmann and his wife Hannah Erdmann in Anatolia,

from the Kurt Erdman Archive, Museum für Islamische Kunst, Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin

Kurt Erdmann was a leading historian of Sasanian and Islamic art (b. 9 September 1901 in Hamburg, d. 30 September 1964 in Berlin). Erdmann’s career and numerous publications were closely connected to the Islamic Department of the Berlin State Museums, of which he was director from 1958 until his death. He also taught Islamic art at the Universities of Berlin, Bonn, Cairo, and Hamburg. From 1951 to 1958, he was professor of Islamic art at the University of Istanbul.

After the completion of his doctoral degree in 1927, he began his career as a volunteer in the State Museums. Working as a curator of European paintings, he was invited by Friedrich Sarre to participate in a major publication on carpets (F. Sarre and H. Trenkwald, Altorientalische Teppiche II, Leipzig and Vienna, 1928), which immediately showed his mastery of the subject. This volume set the stage for modern scholarship in the field of carpet studies.

This opportunity initiated his lifelong interest in the art of carpet making, which resulted in numerous outstanding contributions not only to Persian, but also to Islamic art as a whole. Systematic research into sources, including travel accounts and European paintings, and analysis of carpet patterns, structures, and technical features, led Erdmann to insights on the general history of Oriental carpets, as well as on special groups of carpets. His major works on carpets reached an international public through English translations.

Erdmann participated in xcavations of 1928-29 and 1931-32 at the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon, which had been undertaken by Erdmann’s colleague at the Berlin museum, Ernst Kühnel. This led to acquisitions of Parthian and Sasanian art for the museum, and led Erdmann to a second field of interest. The art of pre-Islamic Persia, especially the Sasanian period, was of great importance for his research during the 1930s and 1940s.

In his study of Sasanian hunting plates, the first systematic work on this group of objects, he developed a chronological sequence according to the compositional features of the king’s crown. His identification of the king in the rock-relief at Tāq-e Bostān as Pērōz (r. 457/59-484; “Das Datum des Tāk-i Bustān,” Ars Islamica 4, 1937, pp. 79-97) resulted in a controversy with Ernst Herzfeld, who identified the king as Khosrow II (r. 591-628). Although Herzfeld’s arguments won wide acceptance, this issue is still a matter of scholarly debate. He was also concerned with the influence of Sasanian themes on other cultures (“Die universalgeschichtliche Stellung der sasanidischen Kunst,” Saeculum 1, 1950, pp. 508-34).

While carpets and Sasanian art were his two main fields of interest, Erdmann wrote extensively on a variety of other subjects, ranging from Achaemenid themes (“Persepolis: Daten und Deutungen,” MDOG zu Berlin 92, 1960, pp. 31-47) to Turkish architecture (Das anatolische Karavansaray des 13. Jh., Berlin, 1961-76). His work at the Museum resulted in numerous publications on groups and single works, indicating his productive scholarship in all media of pre-Islamic and Islamic art (“Die Keramik von Afrasiyab,” Berliner Museen 63, 1942, pp. 18-28; “Islamische Bergkristallarbeiten,” Jahrbuch der Preussischen Kunstsammlungen 61, 1940, pp. 125-46; “Neue islamische Bergkristalle,” Ars Orientalis 3, 1959, pp. 201-205). Many acquisitions made under his tenure at the Berlin Museum resulted in expanded scope, knowledge, and understanding of Persian art in the Islamic period (“Keramische Erwerbungen der Islamischen Abteilung 1958-1960,” Berliner Museen, N.S. 10, 1961, pp. 6-15; “Neuerworbene Gläser der Islamischen Abteilung, 1958-1961,” ibid., 11, 1961, pp. 31-41).

His rigorous and impeccable scholarship has left a lasting influence on all later scholars of Islamic art.